Column: South Asian American culture goes from avoided to appropriated

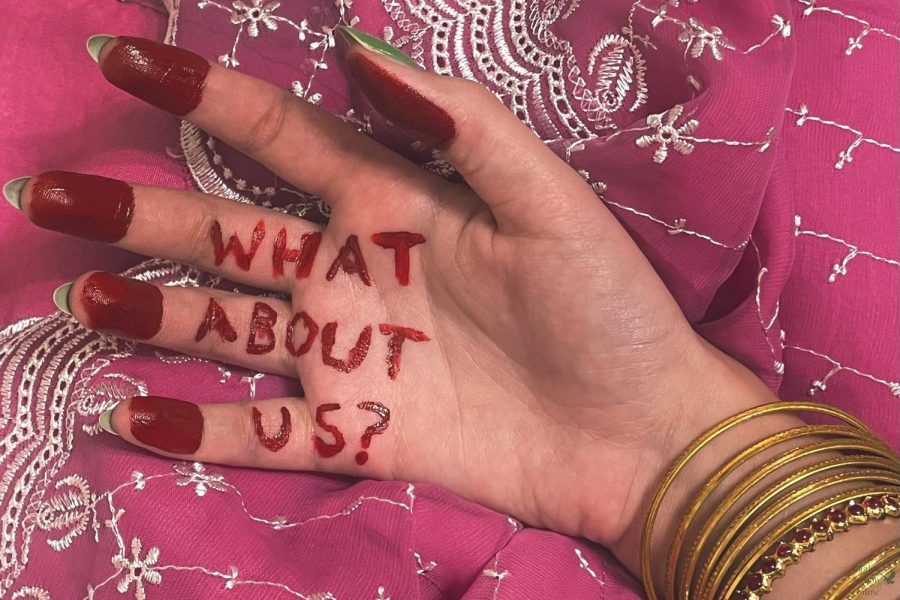

Gold bangles and vivid red paint decorate the hand of half-Indian, half-white junior Kalyani Rao. The words “What about us?” are written on her palm. The red paint is inspired by Rao’s memory of practicing a style of Indian classical dance, Bharatanatyam, as a child, where the hands and feet of the dancers would be painted red before a performance. “Indian culture is so incredibly beautiful,” Rao said. “I’m proud of my relatives from coming all the way to the United States from the vibrant country that is India.”

South Asian American discrimination, stereotypes in media

A well-known character from one of the most beloved cartoon shows of all time — still broadcasting today — Apu from “The Simpsons” is a stereotypical Indian man who owns a 7/11. His thick accent and frugal nature is frequently made into the butt of jokes by the rest of the characters. The white actor who voices Apu, Hank Azaria, finally apologized for his contribution to Indian American stereotypes after 30 years of playing the character. He did so bitterly, claiming that his critics were just “17 hipsters in a microbrewery in Brooklyn,” rather than the Indian Americans who had directly experienced the repercussions of his actions playing an offensive character.

In an episode after the controversy, the issue was directly alluded to through Lisa Simpsons’ words in an episode of “The Simpsons” as she read a book out loud, which had been rewritten to avoid racially offensive language. “Something that started decades ago and was applauded and inoffensive is now politically incorrect. What can you do?” Lisa states, sighing dramatically and staring into a framed photo of Apu emblazoned with the written words, “Don’t have a cow.” The largest religion in India, Hinduism, considers cows to be sacred and holy – the fact that “The Simpsons” couldn’t even throw in a lukewarm apology without adding another mocking joke is telling of the producers’ mindset towards minorities who have been hurt by their show.

Indian characters in American media have been based on the stereotype that they cannot assimilate into American culture since the 90s. Media has portrayed these characters as characterizing something innately embarrassing about having South Asian heritage or living up to the stereotypes that have been placed on them. This is only emphasized by the fact that most Indian characters until the early 2000s have been played by white men.

In “Short Circuit 2,” a 1988 comedy about a robot who befriends an Indian scientist, the Indian main character is played by Fisher Stevens, a white man who darkened his skin and hair for the role. However, we didn’t leave “brownface” — a term referencing the darkening of a white person’s skin in order to look South Asian — behind when we entered the 21st century. Divya Narendra, an Indian student in the 2010 movie “The Social Network,” is played by Max Minghella, who is, again, white. In 2012, a Popchips advert featured Ashton Kutcher impersonating a Bollywood producer.

The main characters impacting my childhood perceptions of stereotypes placed upon South Asian Americans were “Phineas and Ferb’s” Baljeet and “Jessie’s” Ravi. Both boys shared two things in common: a thick accent and a nerdy stature that made them the frequent butt of jokes from “regular” Americans. All of the kids featured in Jessie were adopted from around the world, yet Ravi was the only one who wore traditional clothing and stood out from the others as a foreigner. On the other hand, Baljeet represented the stereotypical math-obsessed Indian kid. In the words of “The America Bazaar,” Baljeet’s concern for his grades is “extremely over-exaggerated.” He puts up “drapes of shame” in his room when he does not do well on a test. His Christmas gift is a calculator.

Children’s shows like “Jessie” and “Phineas and Ferb,” well-loved by the masses, leave deep impressions on kids who assume the racial stereotypes they embody represent the entire race of people they are targeting. Even when I was little, I remember the deep shame that came with being seen as the “other” or the weird foreign kid – I was lucky, in a sense, that I grew up with a white parent, and didn’t have many of the factors (such as bringing ethnic food to lunch) that led to the teasing and bullying other Indian American kids have faced. But, on the other hand, witnessing the way they were treated made me feel ashamed of my own heritage. I grew up thinking that being South Asian was something to be embarrassed about, that we were limited to only being good at math or eating “weird” food.

What carries through into everyday life

For a well-known example, look no further than arguably the most popular YouTuber in the world, Pewdiepie, who has made thousands of dollars off of multiple videos making jokes out of Indians and their “social ineptness” — “show bobs and vegana,” “you India you lose” and “Jai Hind/ I’m half Indian!!” for starters. When you take a closer look at this “dark humor,” the mindset of white superiority shines through. Every possible characteristic of an Indian person has been criticized by Americans, from being hard workers to cultural dishes like curry. When I was in middle school, I remember countless jokes targeted at my South Asian peers referencing Pewdiepie’s jokes about Indians to mock and ridicule them for unwarranted stereotypes.

In her book ‘Indian Accents,’ Shilpa Davé, assistant professor of media studies and American studies at the University of Virginia, looked at the casual xenophobia towards South Asians through what she termed a “brown voice” in American TV and film.

“An accent highlights the norm, and it also points out its own difference,” Davé said. An accent piece of furniture, for example, acts as a complement and contrast to the rest of the furniture in the room. Davé wrote that Indians have been written into popular culture as a sort of accent piece, an exotic decoration that spices things up without being too threatening.

“The way Indians function in representations of Hollywood is oftentimes as an acceptable form of difference,” Davé stated. “Yes, they are different, but it’s a difference that we can accommodate.”

‘Now we want you’: white people pick and choose aspects of Indian culture for themselves

The song “Jai Ho,” created by Indian composer A.R. Rahman for the 2008 film Slumdog Millionaire, was remixed into an American pop version by the Pussycat Dolls in 2009, according to Bhoomi K. Thakore’s dissertation from the University of Chicago. The commodification and re-packaging of Asian culture in Western popular culture is comparable to colonialist practices of appropriating native goods to sell back to their own people. This re-packaging creates a whitewashed and “Other”-ed presentation of South Asian culture.

Now, I could point to hundreds of trends that have stemmed from Indian culture. From yoga, to Hinduism, to chicken tikka masala, to bindis. So many trends have been appropriated from Indian culture and formed to fit white needs without respecting the art’s origins. I couldn’t count on both hands how many white youtubers with sanskrit tattoos preaching Hindu mantras show up when you search “yoga tutorial” or “ayurvedic yoga” on YouTube. Several have over 5 million followers, and one of them starts all of her videos with her ‘catchphrase’ “Hey yogis!” Yogis are ancient Indian masters of yoga, not beginners on Youtube learning how to do downward dog poses. Suddenly, yoga has become a part of whiteness, to the point where when you hear the word yoga the first thing that comes to your mind is a white hipster with dreads and not the vibrant Indian culture it comes from.

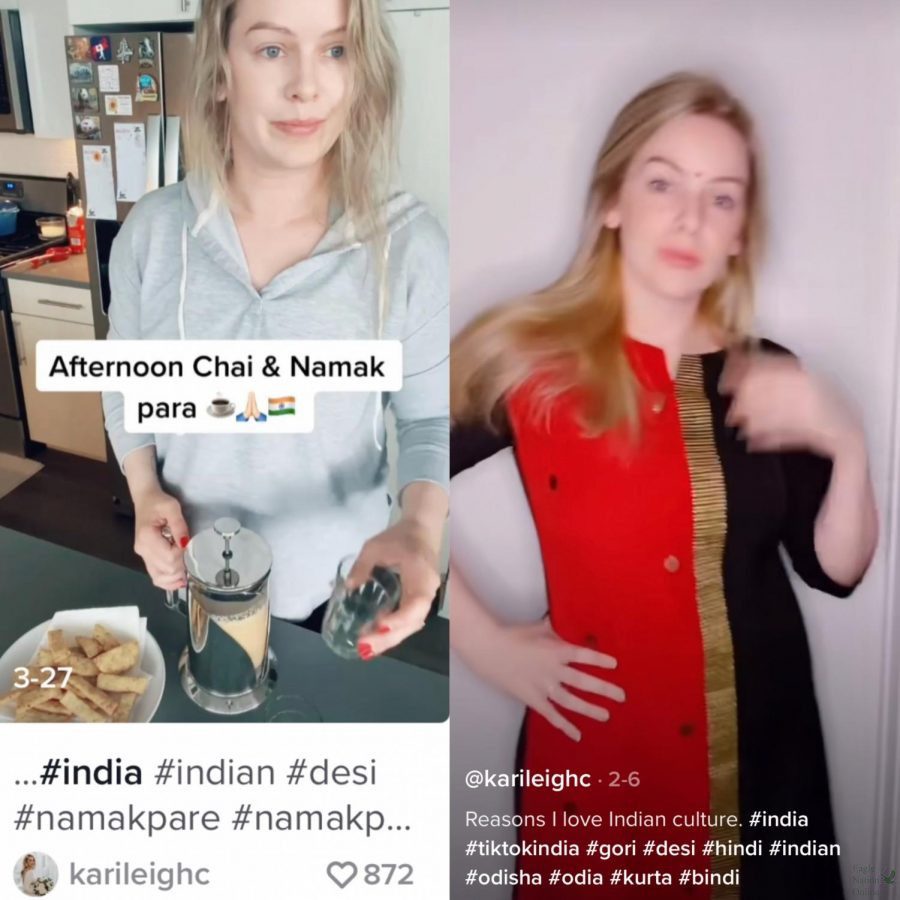

Even South Asian food is cool now, with tikka masala and butter chicken trending as “new great staples” in American takeout. Vegan hipster chains boasting reinvented Indian recipes have popped up in art districts all over the country. What happened to mocking that food 10 years ago? The rapid switch in attitudes is a little disconcerting. Even TikTok is full of white women who have now decided they want to be Indian – many of them pop up when you search “I love India” or “white and Indian couple” – you can endlessly scroll through videos of white women wearing bindis and traditional Indian outfits claiming they’re spiritual masters.

Desi teens share their opinions

Desi refers to people from the Indian subcontinent, including Bangladesh, India and Pakistan.

One of my close friends, who lives in London, wanted to share her opinion on this issue.

“When people talk about cultural appropriation of Asian culture they never mean desi culture,” 17-year-old British Pakistani Almas Shiraz said. “East Asian racism and cultural appropriation is pretty much the only type of anti-Asian racism that’s recognized.”

While it’s a great step forward that we’re making efforts to improve East Asian representation in media and recognize xenophobia towards them, we’re forgetting a massive part of Asia in the process. Currently, the population of India is higher than 1.36 billion people, Pakistan at 216.6 million respectively. There were over 5 million South Asian Americans in the U.S. by 2015, yet they are depicted in less than 2% of all American media overall.

“There’s such a narrow perception of what South Asians look like that everyone’s experience is different, some of us apply to those stereotypes and some don’t,” Shiraz emphasized. “It’s gotten to the point where if you’re a lighter skin tone, or artistic instead of math-oriented, or don’t fit into stereotypes in general, strangers or even friends will make jokes about how you aren’t really South Asian. It’s invalidating and hurtful.”

Desi students also shared opinions on the issue of South Asian American portrayals in media.

“Personally, while I do love having even a small amount of representation of my culture in the media, it’s hard having every desi character be the same,” junior Mithra Cama said. “The characters are always smart, have a thick Indian accent, love curry and are used as a character to laugh at and rarely used as just a normal character like any other actor. I notice these stereotypes used largely on Asians in the media and it can be pretty hurtful when it transfers into real life having everyone think of me in the ways my culture is portrayed in the media. This definitely doesn’t go for all representation, however, and when my culture can be represented how it is, it genuinely makes me feel so happy that I can relate to and be proud of my culture.”

America is known for its diversity, so working to de-normalize stereotypes and accept all the different kinds of people that want to come to our country is important.

“Microaggressions towards Indian Americans are so normalized I feel like people don’t even notice them compared to other cultures,” junior Neena Sidhu said. “It’s something everyone needs to work on, especially in schools because so many people get stereotyped.”

Keeping an open mindset yet being aware of problems is the fastest way to improving issues. By both appreciating the steps forward that we’re taking to help represent South Asians as well as acknowledging and calling out the stereotypes placed upon characters, we can improve our pop culture and society. Bringing awareness to the xenophobia towards South Asians as well as working towards cultural appreciation instead of appropriation is the first step towards a better and more inclusive community.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Prosper High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Honors, Experience and Awards:

5 Best of Sno publications.

5th place in Copy Editing, district UIL meet 2021

Honorable mention- Podcast interview, 2021 TAJE Fall Fiesta

UIL Journalist 2020-2021, 2021-2022

Quill and Scroll Society member 2021-2022

1st place in Copy Editing for CENTEX UIL meet 2021-2022

3rd place in Copy Editing for Aubrey UIL meet 2022

2nd place in Copy Editing for NorTex UIL District meet 2022

National Silver award for poetry from the Scholastic Art & Writing organization

National Recognition Award from College Board

AP Scholar with Distinction Award

2 Best in Texas News & Broadcast Awards, 2022: Personal Opinion Column- Honorable Mention, News Story- Honorable Mention

President of the Classic Book Club, 2020-onwards

Member of the National Spanish Honors Society (NSHS)

PHS Award for Academic Excellence in Newspaper II, 2022

Dean’s Scholarship for Cornell University Pre -College Program

Sibley Scholarship for Brown University Pre -College Program

CIEE Global Navigator Scholarship