Teacher journeys from Marines to FFA

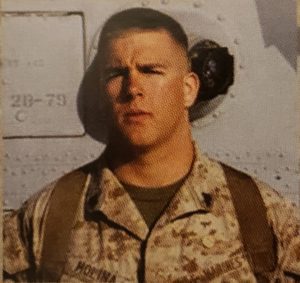

New agriculture teacher Joseph Molina joined the Marine Corp at age 19 and served for five years. He was honorably discharged in 2009 as Sergeant E5. “It’s not for everybody,” Molina said. “It’s a lot of work and a lot of mental stress. If you’re wired that way, and you can contribute to the Marine Corps, and the Marine Corps can contribute to you, do it. There’s risks involved, mental and physical.”

Sleep-deprived and running on a single meal, Marine Corps recruit Joseph Molina trudged up the final hill of the grim 12-mile hike known as “The Crucible.” After three days of braving through rough terrain, extreme weather and mentally challenging teamwork tests, the boot-camp end was in sight. Finally, he reached the peak. The drill instructor placed the ceremonial “Eagle,” “Globe” and “Anchor” into his hands. The journey from civilian to Marine was complete.

“At the end of boot camp there’s ‘The Crucible’, which is a three-day exercise where you march an ungodly amount of miles, and as you go through, you have to solve all these brain tests – when you haven’t slept in three days,” Molina said. “But at the very end, you go up the top of this hill, and that’s where they give you your ‘Eagle,’ ‘Globe’ and ‘Anchor.’ That was the most defining part of it. It’s a really long and sorry three days, but that part makes it worth it.”

Agricultural science teacher Joseph Molina joined the Marine Corps in February 2004 at age 19. Inspired by the 9/11 attacks and the then recently started Iraq War, Molina broke the mold in his family and joined the armed forces.

“We were not a military family by any means,” Molina said. “The war in Iraq had just started not too long before (I enlisted). I never wanted anyone to ever be able to say that I didn’t serve my country when the country needed me. I was pretty high on patriotism at that point.”

He attended boot camp at the San Diego Marine Corps Recruit Depot for 13 to 14 weeks, the longest boot camp of all the military services.

“What they don’t show in the boot camp movies is you go to class during the day,” Molina said. “You learn Marine Corp history for part of the day, and you’re exhausted from running a few miles. Then immediately you have to go to uniform class, then run a bunch more and do push-ups. We’d march a ton, which is very repetitive. I personally didn’t have a problem with it because I realized very early I’m a pretty headstrong person, and it didn’t negatively affect me like it did other people.”

After boot camp, Molina advanced to Marine Combat Training, where non-infantry Marines learn basic combat and weapons skills in a condensed training period.

“You might have heard the saying ‘Every Marine a rifleman,’ meaning they train everyone in the Marine Corps in infantry skills, regardless if you’re a paperwork person or you’re a mechanic,” Molina said. “Physically it’s obviously super hard. Mentally, it’s difficult, but once you realize it’s all a game to make you tougher, it makes your life a little easier. Some people never realize that they’re trying to test you to see what your breaking point is, but not necessarily break you down. So the mental part is I think harder than the physical part.”

Once MCT is completed, Marines move to specialized schools to learn about their Military Occupational Specialty. Molina went to aviation school in New River, North Carolina, for three months.

“It’s basically just like high school, but the only subject you’re learning is the helicopter you’re working on,” he said. “Then, you’re certified to work. You don’t really know anything, but you at least have enough knowledge to start helping people that have been doing it for years. You have a background going into the fleet, but you don’t know anything because you read it all out of a book.”

Molina began as a mechanic on helicopters and soon progressed to flight-line mechanic, a position that specializes in the largest helicopters in the Marine Corps: CH-53 Echos, which have a 73-feet wingspan, and a length of 99 feet.

“You need a skill you can translate outside the military, and I wanted a job I could translate into the real world,” Molina said. “I wanted to work in aviation because as soon as I got out, I could start working on airplanes. You work on the engines, the fuel systems, the flight controls, the transmissions, and while you do that, you can get qualified as an aerial gunner. The helicopter is so big that pilots can’t see behind. Aerial gunners have to tell them on all three sides if they are clear. I was on a cargo helicopter, so we protected the helicopter with guns and protected it during pick up and landing.”

Recalling the first days he joined the fleet, Molina relates his experience to being a freshman in high school. Members of his unit had already been to Afghanistan together, so breaking into that close-knit group as a new Marine, or “nugget,” proved difficult.

“There’s just so much going on around you. When you’re a freshman, you don’t really know what’s going on, and the feeling is kind of the same,” Molina said. “When I got into the fleet, they had just come back from Afghanistan, so they were super tight. When you’re new, you’re not really in the crowd until you deploy. It was pretty intimidating. They ragged me a lot.”

Molina learned quickly through hands-on tasks and watching his fellow crew members. Later, he taught other new recruits the same skills he had just learned a few months prior.

“I was the gopher for probably the first year I was in the fleet,” Molina said. “You just go get tools and you watch and learn everything on the job. Later, I was in charge of the shop. I really enjoyed the teaching part of that which foreshadows where I ended up. That little facet of it, watching the people I taught become the CDIs (collateral duty inspectors), made me feel proud of what I was doing.”

Stationed at Miramar Marine Corps Air Station, Molina spent three and a half years in San Diego and later traveled to Okinawa, Japan, for six months. His crew was part of the Marine Expeditionary Unit, the term for naval fleets stationed in the Pacific and the Atlantic Oceans with numerous Marines on board waiting to respond to a natural disaster or war. Through the MEU, Molina worked on an aircraft carrier for a few months.

“I loved being on the ship, even though everyone else hated it,” Molina said. “I worked night crew most of the time I was on the ship, and there would be harriers taking off, and if you’ve never heard a harrier, it’s the loudest airplane in the world. It was directly above our heads when we were trying to sleep. I loved being able to look out and see nothing all around me. You’ve never seen dark in your life, I promise you, until you’re in the middle of the ocean on a low-light night, and when you look up, there’s countless stars.”

When the Iraq War started, the MEU deployed a third of the unit every six months, so Molina’s crew only deployed in 2008 and spent seven months there.

“We flew from here to Maine, Maine to Ireland – which was cool because I’m Irish, so seeing my home country was pretty neat. And then, we flew into Kuwait, where we stayed for three days and were caught in the worst sandstorm ever,” Molina said. “We stayed there for an extra five days before we could get into Iraq. I was pretty excited by that time. I was in charge of our shop as an inspector on all of our jobs. I wanted to go so bad because that was part of the whole reason why I joined the Marine Corp. We were actually going to do our job in a place where it mattered.”

Molina claims being a part of the aviation wing saved him from facing combat and allowed him to live in a nicer base with extra amenities, such as phones, computers and a Burger King in the cafeteria.

“I was not roughing it in Iraq,” Molina said. “I lived in a mobile home more or less, which is way better than a lot of people in the military, so I can’t complain at all. The cargo helicopter was only allowed to go in green zones, which means safe. We would just fly from base to base resupplying these different units with different stuff, be it bullets, food, or people, all over the bottom part of Iraq in the Al Anbar province. So no combat for me. I could have gone without a gun, and I would have been fine, but I’m glad I had one.”

Flight-line mechanics worked 12-hour shifts, seven days of the week. When not on duty, Molina’s crew would occasionally watch movies and bet on the results of playing cards or digital pinball, but he recalls talking as the main method of passing time on shift.

“Think of all the dumb things you and your friends have said. Now, extend that for six extra hours and seven days a week,” Molina said. “During war there is a ridiculous amount of downtime, regardless of what branch you’re in. If I had a penny for every word I said in Iraq, I’d be a billionaire.”

Everyday conversations and small, silly stories make up some of Molina’s most memorable experiences in the Marines.

“One of the cargo deals, we didn’t know what we were getting, and it turned out to be gigantic pallets of ice – bags of ice – six feet tall,” Molina said. “You’re in the helicopter. It’s 120 degrees. You’ve got three gigantic engines going above you, and you’re wearing a flak jacket, long sleeves, long pants, and you just fly around for six hours. Getting to ride and lay back on the ice, it felt so good. It was the best flight we ever took. I don’t know why that makes me so happy.”

Molina was honorably discharged on Aug. 22, 2009, as Sergeant E5 after five years in the Marine Corps. After a brief stint in manufacturing, Molina attended Texas A&M University-Commerce where he graduated Summa Cum Laude with a degree in agricultural science and technology.

“We had animals my entire life,” Molina said. “We weren’t ranchers or anything, but we always had animals around, and I thought I might as well study something I enjoy. At Commerce, if you take two to three extra classes, you can get a teaching degree on top of (the agriculture degree). I thought if I take two extra classes and get an extra degree and get another fallback, that’s smart. I had no desire to teach at all. Kids are nuts. I didn’t want to deal with it at all.”

Although he returned to the manufacturing industry for a short time, Molina realized his true calling was teaching.

“Senior year, I had an internship as a student-teacher, and I loved it,” Molina said. “I still went out and worked in manufacturing for a year and a half, and I hated my job. I thought, ‘wait a minute, I had a job I really liked. Why don’t I go do that?’ That’s basically how I ended up back teaching.”

Molina taught agriculture classes at Plano Senior High School for six years before moving to Prosper this year. This year, he teaches “Principles of Agriculture,” “Veterinary Medical Applications” and “Veterinary Practicum.

“

“The school I came from, it was only 11 and 12 graders, so I never saw freshmen or sophomores, and I really enjoy being able to work with them,” Molina said. “In the classroom, my goal is to build that community that we weren’t able to get down in Plano. Here we can build a core group of FFA members through our ag classes, and they can grow all four years. We can see them succeed.”

FFA, formerly known Future Farmers of America, is a competitive organization for students interested in agricultural sciences and using that knowledge to solve real-world problems. Molina is one of four FFA advisers this year, along with Jordan Loving, Kaitlin Tyler and Wade Shackelford.

“FFA is a leadership organization that we have here on campus,” Molina said. “Ms. Tyler says that it’s a leadership organization through the lens of agriculture, which I think is a great saying. We have speaking events that teach you how to be a leader. We have judging events that teach you to think analytically, which is something you’re going to have to do regardless of what job you have. I love FFA. I’m in charge of the sheep and goats and this year. If I didn’t do FFA, I would not be teaching agriculture. It’s the best thing we got going on this campus to me. It’s why I do what I do.”

When it comes to a military career, Molina concedes that the mental challenges can break a student if they are not well-informed on the task ahead, which is why he said he is enthusiastic about guiding students who want to join the armed forces. When asked if he knew anyone who died in combat, Molina said he knew of only one individual.

“One, but most of the people I know who have died have committed suicide, which is a huge problem in the military right now,” Molina said. “It’s not for everybody. It’s a lot of work and a lot of mental stress. If you’re wired that way, and you can contribute to the Marine Corps, and the Marine Corps can contribute to you, do it. There’s risks involved, mental and physical. But if you’re willing to take those risks, you have what it takes to become a Marine. It’s just going to take a lot of work to do. Army, Navy, Marine Corps, the Air Force or whatever you want, I’m happy to talk to any student that’s even considering it.”

Despite the obstacles, Molina remains grateful for the lifelong lessons learned in the Marine Corps and is proud to be a part of a greater mission.

“The Marine Corp helped give me purpose. It helped give me tact. It helped give me discipline,” Molina said. “I did really well in college because of what the Marine Corps taught me. It shaped me into who I am and made me a better person. I have as much respect (for the military) as I did before and every person I meet that was in the military. We share something that most people don’t. Now I’m a part of that.”

Updates made on Sept. 26 for corrections to a quote and to change “CBIs” to “CDIs”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Prosper High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.